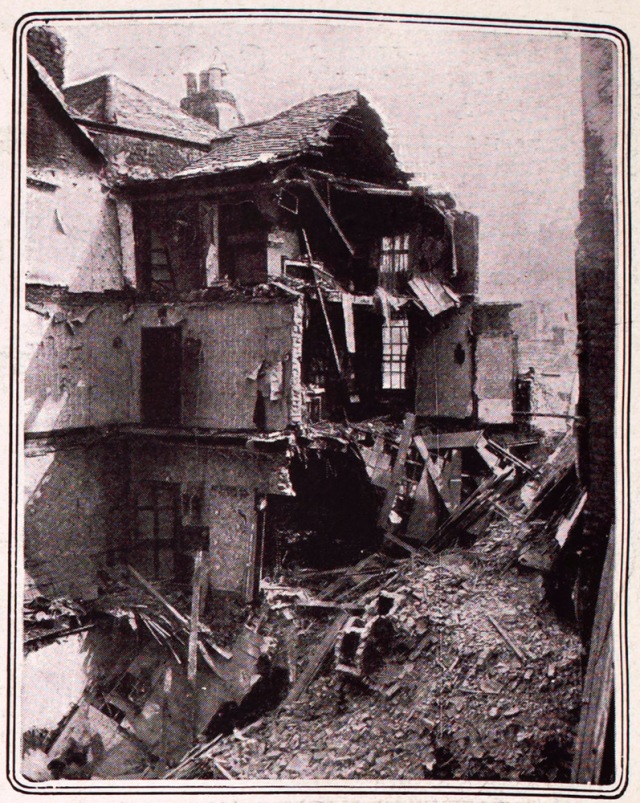

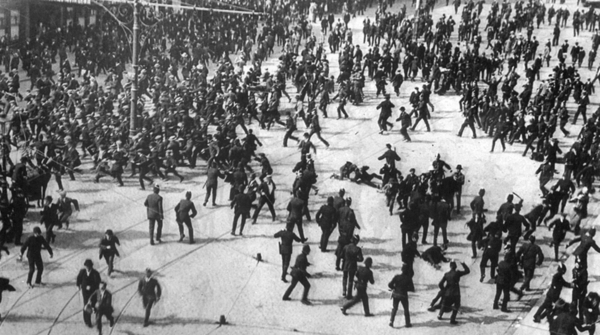

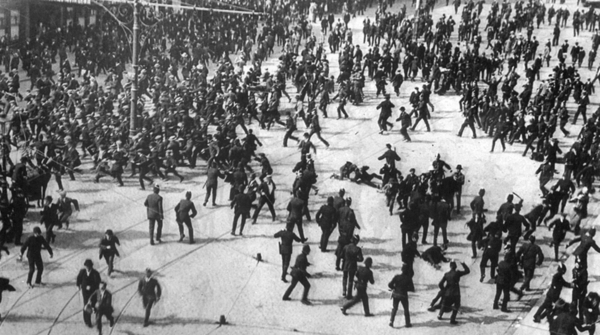

The Bloody Sunday baton charge, Sackville Street, 31 August 1913. Joseph Cashman, NMI Collection.

We are at the 100th anniversary of the 1913 Lockout, undoubtedly the most significant labour unrest in Irish history. One of the most notorious incidents, the DMP Baton Charge, took place on Sunday 31 August in O’Connell Street. The iconic photograph taken by the Irish press photographer Joseph Cashman has somewhat fixed this charge in our minds as a singular event, though it was only one of a series of police baton charges on civilians during a particularly tumultuous and violent few days of rioting during the period. These police batons, one a standard DMP baton, the other a baton of the mounted police unit, were used in the infamous baton charges, and are part of the National Museum of Ireland’s collections.

Dublin Metropolitan Police batons, the Bloody Sunday Baton Charge (NMI Collection)

Dublin and labour in 1913

Dublin in 1913 was a city of contrasting fortunes for its people. Being the second city of the British Empire, it was a centre of business and political power, and a wealthy Catholic elite had emerged. However, Dublin also had some of the worst social conditions in Europe, with high unemployment rates among unskilled labourers, who, when they could find work, endured long hours, bad conditions and low pay. Housing was also poor; in 1911 about one third of the city’s population were living in overcrowded tenements with up to 20,000 families living in a single room. Such conditions led to an increased need for labour to organize. James Larkin, an organizer in the National Union of Dock Labourers, had arrived in Belfast in 1907 to organize a strike there, and was later transferred to Dublin where he, James Connolly and William O’Brien established the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union in December 1908. By 1913 it had about 10,000 members in Dublin alone.

The Employers’ Federation and the Lockout

The main employers in Dublin, seeing the threat of trade unionism as the destruction of the capitalist system, formed the Employers’ Federation. Led by William Martin Murphy, owner of the Dublin Tramway Company, a number of newspapers such as the Irish Independent, and the Imperial Hotel in O’Connell Street, the Federation banned their workforce from union membership, firing suspected members. Murphy himself fired over 300 tramway workers in August, leading to a series of sympathy strikes and the eventual ‘locking-out’ by employers of about 20,000 workers, who were replaced with blackleg or scab labour. The Lockout continued until February 1914, and the interim saw not only extreme hardship for the workers and their families, but also violence on the streets as conflict arose between the workers and the strike-breakers. The British Administration, who had sided with the employers, ordered the DMP to quell the disturbances, and there were in total 15 baton charges during the Lockout period.

The banning of the Sunday Sackville Street meeting

The Union leaders – Larkin, Connolly, O’Brien, P.T. Daly, and William Partridge had held a series of public meetings at the Union Headquarters at Liberty Hall, Beresford Place, in the evenings leading up to the infamous Sunday the 31st, for which a meeting was planned to take place on Sackville (O’Connell) Street. Larkin had already been arrested on the Wednesday, charged with seditious libel, seditious conspiracy and unlawful assembly, but released on bail.

On Friday 29th August E. G. Swift, the Chief Divisional Magistrate, Dublin Metropolitan Police District, issued a proclamation banning the Sackville Street meeting, stating ‘that the object of such a meeting or assemblage is seditious, and that the said meeting or assemblage would cause terror and alarm to and dissension between His Majesty’s subjects, and would be an unlawful assembly’.

That night, the leaders spoke to a crowd of about 2,000 men, women and children at Liberty Hall. Connolly lambasted the ignorance of those who had issued the proclamation, saying that there was no such street in Dublin, and that they would peacefully assemble on O’Connell Street to see if the Government had sold themselves body and soul to the capitalists. Larkin stated that the banning of the meeting was unlawful and publically burned the proclamation; dead or alive, he would address the people on Sunday.

On Saturday afternoon, the DMP arrested Connolly and Partridge for using ‘language calculated to incite to breaches of the peace’. Partridge was bailed, but Connolly refused and was sentenced to three months in prison. Though the police searched the city, Larkin was nowhere to be found. As news of the arrests spread, rioting broke out around the city, beginning in Ringsend and spreading to Great Brunswick Street, where trams came under attack. By 8pm that evening serious riots were taking place around the city, Beresford Place and Talbot Street on the north side, and areas around Corporation Street, Camden Street, Cornmarket and Clanbrassil Street on the south side, and many people on the streets were injured in the police attempts to put down the riots.

-

-

Larkin speaks from the balcony of the Imperial Hotel, Sunday 31 August 1913. Photograph from the Daily Sketch. (NMI Collection)

-

-

Larkin speaks from the balcony of the Imperial Hotel, Sunday 31 August 1913. Photograph from the Daily Sketch. (NMI Collection)

Bloody Sunday

In the wake of Saturday’s rioting, O’Brien feared worse to come and reorganised the Sunday meeting, ordering union members to march to Croyden Park in Fairview instead. At the same time Larkin, disguised as an old man managed to enter the Imperial Hotel (Clery’s), undetected by the police. He gave his speech from the balcony of the smoke room, overlooking Sackville Street. Larkin was immediately arrested and brought to the College Street Police Station.

-

-

Larkin in disguise, speaking to the crowd. Photograph from the Daily Sketch. (NMI Collection)

-

-

The DMP arrest Larkin at the Imperial Hotel, 31 August 1913. (NMI Collection)

As news of the arrest spread crowds gathered in Sackville Street. As tensions mounted, the DMP rushed the street in a baton charge, attacking both protesters and bystanders indiscriminately in the chaos. Rioting again broke out across the city, much of it centred on the north side. The police repeatedly baton charged the protesters, and were themselves under attack from volleys of stones and bottles. The trade union members returning from Croyden Park also took part.

About 450 DMP and 200 Royal Irish Constabulary were on duty in the area, and members of the West Kent Regiment were also called to assist the police in quelling the disturbances. The Irish Times even reported plain clothes policemen armed with walking sticks charging the crowds alongside their uniformed colleagues. The day became known as Bloody Sunday, the first of four in 20th century Irish history.

The casualities

There were many casualties during the weekend of riots. Labourers James Nolan and John Byrne both died of injuries received by police batons on the Saturday, and contemporary reporting stated that 433 people; protesters, constables and bystanders, received treatment in three city centre hospitals; Jervis Street, Sir Patrick Dun’s and Mercer Street. There were many more injured who were not officially recorded and some estimates go as high as between 500 and 600 injured. The violence of the DMP baton charges on the people of Dublin not only tarnished the reputation of the force, but was also a main factor in the formation of the Irish Citizen Army.

The opinion of the establishment

The newspapers, many of which were under the control of William Martin Murphy, were not sympathetic to the strikers. The incidents in Dublin were reported by many newspapers as being the result of the influence of Larkin on his followers, labeling them as criminals, and tended to concentrate on the actions of the rioters. For example, the Irish Times described the scenes on the 1st September as ‘an orgy of lawlessness and cowardly crime. In the worst streets of the city women assisted men in assaults on the police. The innocent as well as the guilty suffered in the confusion of the fighting’. Political opinion too was not favourable towards Larkin and the ITGWU. They viewed Larkin, as did the employers, as a dangerous socialist whose aim was to destroy capitalism and the social status quo. Even the nationalist M.P.s regarded trade unionism as a particular worry at a time when the issue of Home Rule was still being fought for. The British Trades Union Congress went as far as to disown Larkin at its conference in December 1913. With this lack of support the Lockout was in the end a failure, with the employees eventually returning to work in early 1914 with little to no rights won.

DMP baton, standard issue. (NMI Collection)

The Dublin Metropolitan Police batons

The DMP batons themselves were a standard issue to the police force. The Dublin Metropolitan Police, established in 1836 to police the city and modeled on the London Metropolitan Police force, were not armed with firearms like their counterparts in the Royal Irish Constabulary. Instead, constables were equipped with wooden batons to be used only for self-protection and in the apprehension of criminals. They are made from a hardwood such as teak, turned with a ribbed handgrip, often with a leather wrist strap, and stamped with the constable’s police number. The standard issue baton is 48cm long, and the mounted police version is longer at 62cm, and was issued with a leather holder. Each is fairly heavy, and I have heard of a belief that lead weights were inserted inside. However, the batons are clearly turned from a single piece of wood, with no joins, so this is a myth.

DMP baton, mounted police unit. (NMI Collection)

The National Museum of Ireland will be exhibiting the batons, along with other unique objects from the period, as part of its new exhibition on the 1913 Lockout in Collins Barracks from September 2013.

Brenda Malone is a historian with the National Museum of Ireland, and writer of The Cricket Bat That Died For Ireland blog, which explores the Museum’s Historical Collections. www.thecricketbatthatdiedforireland.com

With special thanks to Lar Joye, Curator of Arms and Military, National Museum of Ireland.

Further Reading

- Lockout: Dublin 1913. Pádraig Yeates. Gill & Macmillan Ltd., 2001

- A Capital in Conflict: Dublin City and the 1913 Lockout. Edited by Francis Devine. Dublin Corporation Public Libraries, 2013

- Dublin 1913: Lockout & Legacy. Gary Granville. O’Brien Press Ltd., 2013

- The Dublin Metropolitan Police: A Short History and Genealogical Guide. Jim Herlihy. Four Courts Press Ltd., 2001

Strumpet City by James Plunkett, this years’ One City, One Book choice, is also great for an insight into the impact of social conditions and the effect of the Lockout on the people of Dublin in 1913. Read Garrett Fagan’s Blog post about Strumpet City on our blog.